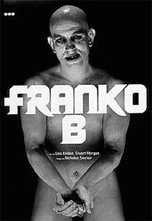

The Illustrated Man: Franko B

Stuart Morgan (1998)

published in Franko B (Black Dog Publishing, London, 1998)

Part of what art is about now is to find ways of beginning to say things about the darkness of culture.

- Susan Hiller

At the end of the twentieth century, art's function can be summarised in the simplest way: to help viewers to imagine the worst before it happens. For as history teaches, the last years of any century are a time of pondering the end of things - even the fate of the universe itself. But such thoughts are far from new. For example, the idea that millennium coincides with apocalypse is at least a thousand years old. In the year one thousand, mid-European peasants left their villages and danced night and day until they died. Though this is unlikely to happen in the year 2000 history shows that one by-product of the millennium will almost inevitably be a return to religion, or at least to ideas of spirituality in general. In other words, the possibility of the end of time will involve changes of heart. "All literature is probably a version of the apocalypse…" wrote Julia Kristeva in her book Powers of Horror. But in order to test this proposition about beginnings, middles and ends, a single example may be necessary, preferably one near at hand.

In a small flat situated in the very middle of London, not for from the Houses of Parliament, lives a young Italian, Franko B, who surrounds himself with objects which fire his imagination. Such keepsakes have long ago overwhelmed his living—space. Franko’s taste does not always coincide with other people's. [Along one side of the largest room, for example, a metal urinal has been attached to the wall]. If a single influence predominates in such art, it is Punk: a style or movement based on the articulation of disgust. So it is hardly surprising that a strong sense of outrage is also vital to the meaning of Franko’s work. For example, in the photographs of himself in a frieze on the wall one particular image recurs. It is that of a wheelchair, for the reference to paralysis, which in this case could be regarded as a social paralysis, seems fundamental to his way of thinking about his fellow men. For at any moment, he seems always to be reminding himself, the human body may either rebel or deteriorate into a lump of useless flesh. The process will probably be slower than that, however, for the wheelchairs in which he likes to sit suggest a situation halfway between activity and stasis. Considered one by one, the wheelchairs in Franko’s collection resemble oddities, symbols of blockage, but mainly of partial impotence. For example, in what might be regarded as a homage to Hermann Nitsch, his compatriot, Gunter-Brus, and in particular the late Rudolf Schwarzkogler and his series of Aktionen (1966-1968), performances made deliberately to be photographed, Franko’s face and upper body are swathed in white cloth as he broods in a corner, arms crossed, a skylight above him and a bag of blood connected to his left arm.

At other times his poses seem vainglorious. In one, he stands on a small truck, his legs pinioned and the whole upper part of his body, including both head and arms, swathed in white bandages, another image of impotence, though in this case a slightly comic or even pathetic one, reminiscent of a living statue. Not every pose is sad, however. Luxuriating in a wheelchair and wearing a gas mask, Franko B strokes both sides of a narrow corridor simultaneously, his legs wide open and a bottle of blood ready for transfusion. [One comparison might be with the activities of Rebecca Horn, some of whose early works involved standing in the middle of a space and using arm extensions of her own design in order to be able to touch both walls of her room at once]. In another photograph, Franko is shown thinking hard. A wheelchair and crutches are visible, while in metal panels pinned to the walls, objects and pictures have been inserted. It comes as no surprise when the artist himself appears in the foreground, lost in thought. On another wall a collage takes the form of a bulletin—board with family pictures pinned up next to playing cards with nudes on them; drawings; old shoes; a postcard reproduction of the Charioteer of Delphi; a street sign; a figure dressed like a frog; an entry ticket to the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London, a place where he himself has performed.... In other words, an attempt to make a kind of portrait of himself. This might be one way of describing it. What keeps his audiences satisfied is his willingness to try to cheat death time and again, perhaps as a demonstration that human beings may be far less fragile than they supposed. In fact, he could have devised his stage act precisely to put this idea to the test.

As the doors open and viewers file info the auditorium, they are greeted by loud Wagnerian music. In a deep, murky space a naked man, Franko himself, makes his way towards a spotlight. As onlookers realise that he is already bleeding from both arms simultaneously, the mixture of powerful reactions is overwhelming—disgust and compassion certainly, but most of all powerlessness and inability to prevent the inevitable: a quick death, but a comparatively peaceful one, due to loss of consciousness. Indeed, the length of each performance depends on how long if takes for a single, increasingly frail being to drop to the ground and lose consciousness. ‘But that does not happen for some time. Arms dangling by his side and pools of blood starting to form of his feet, Franko adopts a pose which has long been commonplace in the religious art of the West. With palms held upwards, a powerful spotlight shining from above and an artificial mist hanging around his naked body, he seems To be imitating an accepted posture of the risen Christ of The New Testament. In another, more humdrum sense he is displaying parts of his body, as a conjuror might, in order to demonstrate once and for all that no trickery is involved. The flow of blood remains unstanched. And of course, as Franko loses blood, he also loses strength. By the end, he is on his knees groveling, palms raised, smoke blurring his outline, while dry pigment on the floor combines with the blood to make an unexpected parody of orthodox painting techniques. Metaphors arise faster and faster still. Groping his way forward Through whaT has become a heavy mist, he resembles a World War I soldier in the trenches, perhaps poisoned by mustard gas.

By this time if is impossible to block other classic images which spring to mind as Franko performs. [Hans Namuth’s photographs of Jackson Pollock, for example, remain relevant]. And as the performance continues, the proceedings become more hectic. No longer capable of standing, Franko mixes his own blood with raw pigment. Then, as he crawls across the stage on all fours and a white mist begins to overtake him, his movements become more frantic. By this point he ignores the audience altogether. In addition, the marks on the stage have come to resemble obliterations, so if there had ever been a message to be transmitted by this point even the most hard—boiled viewers would have realised that this is not acting. In brief, the entire scenario resembles the last minutes of a bullfight. He is losing blood quickly. As much to stanch the flow as to prolong the action, he grabs a piece of rag, rams it info his mouth to absorb the blood, and then, on hands and knees, makes one final attempt to signal his message before collapsing head first on to the stage. Apparently dead, he is dragged away by assistants and with this gesture the event is over. For obvious reasons there is no encore. After the music has reached its crescendo, the audience disperses in silence, pondering on what they have witnessed.

Analysing such an event is difficult. Could the theme be death itself? Or perhaps same procedure by which to parley with it and hold it at bay, like the speaker in Sylvia Plath’s poem Lady lazarus who boasts that she is capable of dying regularly and ‘well’? Bearing this in mind, could Franko’s theme be that of rebirth? At one point in his performance, for

example, he rinses his hands in blood before emptying the entire contents of the bowl over his head, a tableau in which he seems to be_ coming to terms with some private drama of his own. Throughout images spring to mind unbidden. Indeed, they sometimes turn out to be so striking that they usurp the action. For example, at this point in history, the image of blood is impossible to disentangle from arguments involving AIDS. Franko B is seen covered in gore which, it must be emphasised, is his own. [It is also worth remembering that Franko B's personal doctor is present at the side of the stage for every moment of every performance and that, to allow his body to recover, the number of Franko’s appearances is restricted to no more than three a year]. The order of events recalls the crucifixion, and the Christian need to celebrate and emulate that event in afar more vivid form than usual, like a Passion played in some obscure area where local villagers themselves act out the life of Christ. But is it likely that the failure of traditional religion has to do with the sense of intimacy which Franko B is able to convey? For he is remarkably forceful, given that what he suggests is an alternative which some would describe as self—mutilation. Others, however, would be relieved by the prospect of a real rather than imaginary biblical figure being willing to die for them, a surrogate willing to relieve travelers of their heavy burden—including, perhaps, even life itself.

As interesting as the symbols used in his performances are Franko’s tattoos, still unfinished but nevertheless providing enough hints to enable one to imagine the entire design. Around one nipple a mouth, eyes and nose can be discerned. The other has a design in the shape of a vortex or a comet whirling in space, flanked by what resemble Russian Constructivist decorations. On the shoulder above the laughing mouth another vortex appears, like an ancient Chinese motif. Around the pierced navel one more decoration has been added, with eyes, wings, and a face gazing upwards, making the impression seem more demure. In addition, crosses and pluses form part of the overall scheme, one which promises to run from head to toe, and to be intricately planned. Franko’s fingers are decorated with simple, individual motifs which could be integrated at some later time. Emphasis is given to designs which are bold, large, often almost totally abstract and deeply coloured. The conclusion seems elementary: tattoos exist to be admired for they provide a different angle on wearers and watchers alike, and one that can help in bringing people together. At the same time, it could be argued, they do exactly the opposite, scaring others away by means of the grotesque. [In this case, a kind which cannot be easily eradicated].

Wearing black boots with callipers and nothing else, Franko B sits in a nondescript white space, waiting as beggars do. In another photograph, he is lying in the open air in the same way Chris Burden did when he lay naked on a California freeway at night, head down and covered by a tarpaulin. In comparison, the area Franko chose for one of his own bleak performances had recently been the site of the most famous eyesore in London: a huge concrete underpass overlooked by the grand, main door of Waterloo Station. ‘Cardboard City’ was a place which had once sheltered hundreds of homeless people living in boxes. in other words, the area was chosen by Franko B because it had once been the site of an historical scandal to do with poverty. In such places, graffiti can be a quick and useful means of communication. But not in cases like this, where messages on walls are written backwards, not in full—blown language but rather as an exercise in obscurity. In New York in the 80s graffiti gangs vied for notoriety by devising and employing private sign- systems, complete with ways of allowing them to develop. Here, in contrast, only three hundred yards from the Houses of Parliament, a crude stick figure was drawn on concrete, with a halo around its head and an explosion going on in its hands. Next to it, Franko B stands naked from the waist down, with his legs in callipers, a bag over his head and a hot water bottle which he cradles as if it were a baby. Childish’? If a single visual influence predominates, it might be the Theatre of the Absurd, with its decidedly juvenile tendencies. For example, in another photograph, for which he is also naked, Franko has coincidentally been photographed next to huge graffiti. “FEEL”, says one. “ART”, another proclaims. Unable to respond, Franko stands to attention, unclothed, as if waiting for something? Could it be that together the words “FEEL”, “ART” and “PAINT” constitute a manifesto for what he is offering?

But for that matter, what is Franko B offering? Is he merely annoying the bourgeoisie, in this case by being even more vexatious than usual by employing classic avant-garde methods? (One definition which, though truthful, ignores the danger of his actions). Another would be to regard the entire exercise as an example of penance leading to grace. In particular, the act of wetting the head and body recalls the Christian ceremony of baptism. No doubt an element of spectacle for its own sake is also present - consider sword-swallowers or high-wire artistes - leaving the audience in a quandary about the tone, and therefore the significance, of the event. But there are other ways of analysing Franko's invented ceremony. The photographs show how little we have, living in a labyrinth where ideas and realities of the body have become extreme - take Stephen Hawking, take any fashionable rock band - so much so, indeed that we have been forced to revise our definition of health. The masochistic poses in which Franko B indulges call to mind important and difficult arguments, notably those involving the individual's right to opt for suicide. On the other hand, this work could hardly be more optimistic, given the circumstances in which he has been placed. For Franko, concrete is not brutal but honest, and the architecture has to stink of urine. But despite the fact that his stage act ends when he is dragged away to be ministered to by a doctor, the significance of the entire event is much greater than this. After all, death remains the great taboo.

But how much does the apparent childishness of Franko's message matter? The half-naked men loitering in underpasses, the historical references to Viennese Actionism of the 60s and 70s, the use of visual provocation in public places and the undecided role of violence are all questions that beg for answers. First, the continued role of the body at its most vulnerable needs explanation, and secondly the historical forerunners of Franko's type of work must be discussed. All roads lead to Vienna, for the importance of the body was paramount in Viennese art of the 1960s, when figures like Hermann Nitsch with his Orgies-Mystery Theatre proposed a wider view of the tachiste painting technique with which they had become accustomed, and expanded it into three dimensions. One result was that art inched gradually towards three-dimensionality while the role of the audience assumed ever greater importance. The result was a Gesamtkunstwerk, for people moved nearer to the art, and even formed part of it when it was made public. Another strand of Viennese body-work was more solitary and demented, however, like that of Rudolf Schwarzkogler, who fell to his death from a window after a spell of severe dieting. Franko B's position may be described as situated halt—way between the two.

Franko’s manifestations involve a critique of housing and of the powerlessness which is concomitant with metropolitan life; of the importance of self—definition; of appearances and what they conceal; of politics and the need for free speech. At the core of his thinking, however, may lie a powerful statement about ritual and its uses: on the one hand Christ crucified and its possible meaning today; on the other a manifesto about homelessness and its effects on daily life: about-what should be seen and what should remain hidden; but most of all about the uses of ritual. Organised religion is failing badly. Franko’s answer is an old one: the imitation of Christ, which some would condemn as blasphemy. Art, too, may be failing in its task of defining beauty, an aspect of aesthetics which has been forgotten, even derided. Franko’s own statement RlTUAL/FEEL/ART could refer simply to his own manifestations. [in stinking, labyrinthine underpasses, for example]. But it goes further still. As an introduction to his public displays, it suggests first a visceral response and second a thoughtful one, with reality to the fore and the time—honoured ways of worship linked to icons. Franko makes himself one of those icons, acting as a contemporary Christ—surrogate, as well as an image of the crucified Christ. Could this be blasphemy’? Or simply an unexpected way of practising religion? For ritual and feelings that have been forced apart are meant to be amalgamated, as Franko’s triple injunction tries to explain, and perhaps only the idea of an artist/icon can heal the rift.

publication:

related works:

-

• I'm Not Your Babe

performance (1995-1996)

-

• Mama I Can't Sing

performance (1996-2000)

-

• Early works for Camera

performances for camera (1988-1996)