Untouchable: The Three-Dimensional World of Franko B

Michele Robecchi (2010)

published in I Still Love [24 Ora Cultura, Milan] (2010)

Diversity can often be a double edged sword in the practice of an artist. Luc Tuymans moved from filmmaking to painting at the end of the 80s – a move initially looked at with a certain suspicion. Only later on, when it was evident that his stylistic choice had a solid conceptual base, did his earlier work regain a reputation for being something more than just a cunning strategy, winning the universal approval of both critics and the public. Damien Hirst also complained of a similar situation when he started working on his first spot paintings in the mid 90s. Public opinion was split between the optimism and the simplicity of the multi-coloured canvases and the dramatic intensity of his dissected animals preserved in formaldehyde.

If taking on painting is an almost natural course of events for an artist and is generally appreciated even by those who initially gave it a wide berth, moving away from it is another question altogether. Painters rarely depart from their media of election and when they do, they mostly tend to embrace sculpture, where a formal quality can be preserved even in the most experimental moments, as the work of artists like Jannis Kounellis and Anselm Kiefer testifies.

When it comes to performance art, the question is slightly more complicated. A shift of this kind is almost inevitable, partly due to the immediacy of the media itself, and partly because the physical ageing of the artist is a factor that needs to be taken into consideration. With the exception of Marina Abramovic, who continues to perform new and old pieces to these days, a whole generation of performance artists have, over time, stopped performing and turned to more object-based art. One of the main issues here is that the new work rarely has the same explosive impact of the old one. Chris Burden crucified himself on a Volkswagen and was shot at in a gallery; Vito Acconci masturbated under the floor during an opening or shadowed passers by for hours; Valie Export walked amongst the audience inviting them to touch her, or entered a theatre tooting a machine gun and wearing crotchless overalls. Performances of this kind are destined to leave a deep mark, as well as to form a crucial moment in the career of the artists themselves. The spectator gets used to a level of audience participation that cannot be sustained for too long. In the most fortunate cases this can be defined, in simple terms, as the syndrome of the masterpiece. If artists wish to preserve the same level of integrity that they have reached in their early work, they can turn it into an obsession or they can try to move on to new directions, but they cannot ignore it. A successful piece of art is a mixed blessing for its author. It can become either an alibi or a curse, and it’s a phenomenon extended to all art disciplines.

For an artist who always had a multidisciplinary approach to art like Franko B, the problem can be even more insidious. There is a tendency to confuse what’s complementary with what’s superfluous, and to treat any diversion from the main theme with diffidence, instead of perceiving it as a vital component to understand the whole picture.

Franko B started working with performance in the mid-90s, at a time when the London art scene seemed to be moving on towards other forms of expression. The new English art, backed by the driving force of the YBA, was aiming for a direct confrontation with the spectator through fairly conventional means. Even in the most radical cases, the adopted forms had to be accessible, and in many instances, purchasable. It is also important to remember that in contemporary art, performance often represents the way in for the outsider. There are many reasons for this. It’s a practice naturally inclined to establish links with other creative disciplines; it’s free from many of the constrictions dictated by art spaces; its fruition is immediate and time-limited; and it’s not financially demanding. Francis Bacon once said to David Sylvester that one of the reasons for taking up painting is because it’s cheap. [1] Franko B moved his first steps by adopting a hybrid language midway between the suggestion of Bacon and performance art. His actions involve the use of his body as a canvas. The white pigment covering his skin was slowly coloured in red by the dripping of his own blood, creating a contrasting image of solemnity, violence, beauty and terror.

The power of Franko B’s performances has been discussed at length. They have often been historically linked to Action Painting or Viennese Actionism, although the origins, more than anywhere else, should be tracked down to his biography and the Italian and British cultures that characterize him. London was a culturally mixed city when Franko B moved there in 1979. The nihilism of punk was beginning to morph with the elegant decadence of Neo-Romanticism, and the early signs of Thatcherism, which would eventually throw the whole country into a period of austerity followed by an economic upturn, were in sight.

Franko B brought with him a classical vision of art, closely influenced by the Renaissance and religious art. It’s a heritage that generated some of the most memorable milestones in the history of art but at the same time, it creates a kind of conditioning for an artist from which it is difficult to emancipate completely. The combination of an urban dimension with a spiritual one is undoubtedly one of the main elements that inform Franko B performances, and it is also the key to understanding his practice as a whole. A strange combination of mannerism and street life is already visible in his early collages of the mid-90s, and especially in the photographic series “Still Life” (2003), where images of homeless people and urban decay were shown in a new light that conveys an unexpected dignity without incurring in a cynic or banal representation of the aesthetics of pain.

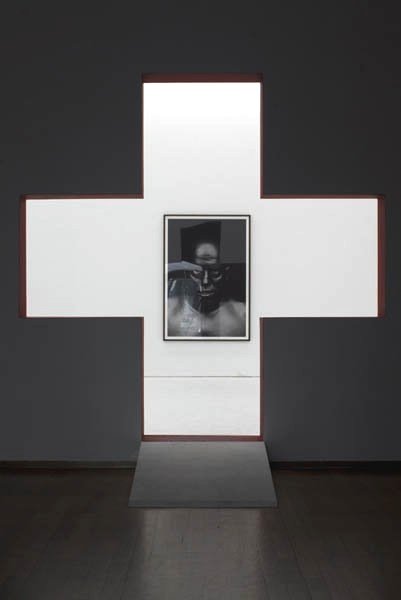

His three-dimensional work was also based on similar premises. The streets of London’s East End don’t have the elegance and grandness of their Western counterpart; their richness is the vast multiethnic heritage, the social diversity and the irregular, often incomplete architecture. Modern buildings alternate with others that have not yet been properly rebuilt after the Second World War. It’s in this colourful setting that Franko B started working with sculpture alongside his photographic work. Objects of different provenience and meaning were collected by the artist during the day and night and then brought to his studio where they waited to find a place in his artistic world. A first step in this direction was the creation of ‘environments’, as the one shown at the Home Gallery in London in 2001. The transition from performances to sculpture was crucial. The actions of Franko B were in fact mainly focused on the artist himself, with the body playing a leading role. At the moment of translating this philosophy into a two or three-dimensional form, the presence of their creator became more subtle. His early paintings were mostly red and white – the trademark colours of his performances; alternatively there were self portraits and portraits of people close to the artist. In his sculptures, apart from some exceptions like the self portrait created for his one man show at Galleria Pack in 2004, Franko B’s figure was a discreet presence, which highlights yet again how a limit can be turned into an advantage.

At first glance, some of the key aspects of Franko B’s work, such as blood, the body and a rather confrontational approach with the viewer, are somehow diluted. However, a closer look reveals how his sculptures communicate something that the theatricality of his performances used to disguise or push into the background. The vulnerability of the human condition (a favourite theme of the artist) assumes an unexpected delicate form, with his sculptures maintaining a surprising innocence, even when they’re painted with the blood of the artist – a gesture that could easily lead to an atmosphere of trash or decadence. There is genuine affection in the art of Franko B, a strange kind of love and gentleness that affect everything that surrounds him. A clear example of this are two recent sculptures made of pieces of church furniture that the artist found in Italy, saving them from destruction.

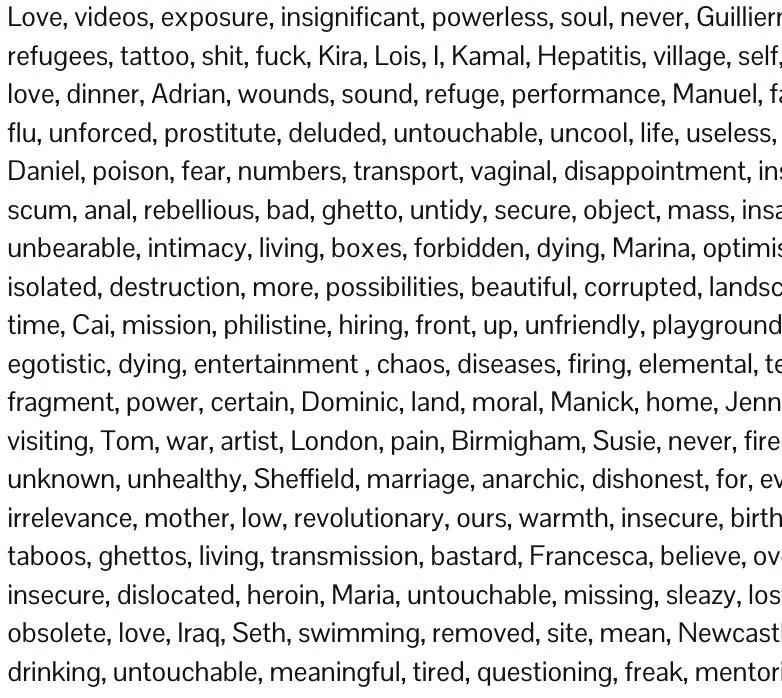

The first one, which is relatively simple, consists of a group of church pews with kneelers. Decontextualised and stripped of the presence of churchgoers, it opposed the initial designation of religious gathering with a strong sense of absence. The second one is a confessional that the artist has repainted completely in gold. Both pieces project a nostalgia that even their kitschy new colour cannot undermine; but whilst the pews refer to a collective moment, the confessional investigates something private. Confession is a predominant symbol of the catholic religion, but as even the most infrequent church-goer will have noticed, it’s gradually losing popularity, with the result that today a confessional is little more than a decorative ornament, just as the organ or the pulpit. The idea of kneeing down and completely opening up in front of a stranger is not particular appealing, but it’s a familiar concept in the art of Franko B. As in every ready-made, the physical intervention of the artist is minimal, but the conceptual implications of this non-gesture are enormous, and give strong evidence of Franko B’s stylistic maturity as a sculptor. The confessional piece is a concentrate of vulnerability, faith, sacred and sin – a monument to what is unsaid but well-known and vice versa. Years ago Franko B wrote a poetic manifesto of his art; a long list of objects, people, and words that synthesised his complex path with absolute honesty to himself and others. Partially deprived of its austerity, the confessional is now a less intimidating presence. Just like the rolling credits of a film, while looking at it, one can almost hear Franko B reciting ‘Love, videos, exposure, insignificant, powerless, soul, never…’ [2]

notes:

[1] David Sylvester, ‘Interviews with Francis Bacon – The Brutality of Fact’, Thames & Hudson, 1988

[2] Franko B, ‘Untouchable’, 2009

publication:

related works:

-

• I Still Love

exhibition (2010)

-

• Untouchable

text (2009)

-

• The Golden Age

series of sculptures (2007-2008)

-

• Circle Paintings

acrylic on wood (2004)

-

• Still Life

photographic series & book (2003)

-

• Volume 2

exhibition (2004)

-

• Oh Lover Boy: The Exhibition

exhibition (2002)

-

• Blood Canvas

series of collages and wrapped objects (1999-2003)