When There’s No Future, How Can There Be Sin?

Becky Haghpanah-Shirwan (2015)

The life and work of Franko B is situated somewhere between isolation and seduction, benevolence and confrontation, suffering and eroticism, punk and poetry. It is a certain type of schizophrenia that finds a balance, dramatically undermining the status quo.

‘There is this ghetto in the art world which says that if you are “expressionist” you must only be that,’ he asserts with respect to the marginalizing effects of conspicuous popular labeling. ‘Why close stuff in a box? Artists benefit from creating environments where anything can happen and there is contamination involved.’ Performative, rather than a performer, Franko B moves between mediums to sculpt the audience through the purity of their visceral connection. Stereotypes and categories sit in stark contradiction to his organic existence, as the ambiguity of the distinctions becomes his practice. Performance? Queer? Pleasure? Pain? His position is thus: ‘I don’t wish to be included in your ghetto mentality and fetishisation of where I might come from. I don’t have anything to prove to you or anything to justify so just fuck off.’

Fuck poverty; Fuck your democracy; Fuck what you want. The Fuck series, comprising 15 pieces, featured at the core of Woof Woof I’m Back!!, a solo exhibition at Mayor’s Parlour Gallery, London in February 2015. A body of over 80 stitched works was on display, representing myriad themes from his life, his love and his biting satirical humor. Marking his resurrection, Franko B announced ‘the old dog’s back’, with a noticeable paradigm shift towards a new conceptual mantra: the personal, political and poetic.

The nihilism expressed through his recent stitch works is testament to Franko B’s anarchism, born from the Punk era in London. The preoccupation with latent hypocrisies informs Franko B’s commitment to authenticity and the politics of misrepresentation – an agenda and ideology at the heart of the punk scene. Moving to England in the late 1970’s, Franko B joined anarchist and pro animal community in Brixton, London ‘I was a very political person, I was an anarchist and an anti fur and vivisection punk and took part in manifestations regarding these issues… I was supposed to serve in the then obligatory army national service, but as an anarchist I decided to avoid this...’ he recounts. The chance to promote freedom, progressive sexual practises and anti-establishment sentiment seduced him. Caught up in the non-conformist scene of S&M, tattoos, drugs and hard techno, Franko B found his iconoclastic core. His recent works reveal a complex dialogue with the existentialist crisis of the Punk era. Sewing a series of statements, the iconography of his biography, politics and porn onto paper, the production is modest and the dimensions standardised. The anarchist self-restrains his autonomy to remind us: freedom is a choice.

In the early 90’s Franko B performed on stage at an S&M club in London. Sitting in a wheelchair and breathing into an oxygen mask, he was lead out by a woman dressed as a nurse. Cutting blood and urine bags [his own] away from his body, he threw them into the audience. ‘I wanted to talk about the contradictions in the gay scene’, Franko B remembers. The pseudo-machismo of that time within the bodybuilding and muscle men scene was counterpart, but oblivious to, the tragic reality of the AIDS epidemic. Presenting his body in a failing state, the performance confronted the audience with a palpable representation of the real - a stark reminder of their own mortality.

This visualization of the corporal reoccurs in his performances, notably in the iconic I Miss You in the Turbine Hall at Tate Modern, 2003. Franko B walked the runway, illuminated by florescent tubes. Blood flowed from his veins, dripping over his naked white body and onto the canvased floor. Isolated and exposed on stage, his blood was offered as a reflection of society’s vulnerability. ‘We are all bleeding inside’ Franko B avowed. The personal became materialized; humankind personified. By performing the self, Franko B entered a history of art saturated with politics. However, his objectives transcend his predecessors. Unlike artists such as Marina Abramović, Chris Burden and Gina Pane who suffered and shocked to disrupt the social malaise, Franko B’s work conveys a genuine benevolence to unite his fractured audience.

‘The artist is a poet who is able to appropriate language that already exists in the universe and briefly make it their own … but it is their own just while it is in their consciousness. From the moment it leaves the body it becomes another person’s language - a form of collective language’, Franko B states. Interestingly, it is the complexity and range of emotional responses to his work that forms the collective language. Exploring Guy Debord’s theory of the spectacle, Nato Thompson relays ‘Given the market’s near total saturation of our image repertoire – so the argument goes – artistic practice can no longer revolve around the construction of objects to be consumed by a passive bystander. Instead, there must be an art of action, interfacing with reality, taking steps – however small – to repair the social bond.’ Indeed, Franko B’s work forges through the extremities of late Capitalism, forming the bond by provocation of the audience’s collective anxieties. Democratized through the body paint, white washing his remarkable idiosyncrasies, Franko B bled for us as an antidote to the spectacle; today, his medium changes but the wounds remain. By so doing, he selflessly positions himself as a conduit via which we engage with the emotive truths of our own existence. He states ‘I believe in beauty, but in a beauty that is not detached from life. My concern is to make the unbearable bearable, to provoke the viewer to reconsider their own understandings of beauty and of suffering.’

The ‘unbearable’ permeates from his troubled childhood, spending his formative years in orphanages and on the streets. This primary detachment and isolated existence now manifests through his obsession with love, enduring honesty and continual self-sacrifice in his borderless network of art and life. The echoes of his past are witnessed in Still Life, where Franko B walked the streets of London between 1999 and 2002 photographing the homeless from a distance. As the onlooker observes, only traces remain of a marginalized few, ignored or overlooked by passers by. Society detached. Leaving the subjects with a rare sense of dignity, their faces are never seen. Franko B disappears, confronting the audience with the paradox of their own conscience, forced to question their individual responsibilities in this uncomfortable power dynamic. The sobering reality surfaces: although we walk the same streets, we essentially remain alone. Projecting the confluence of love and pain, Franko B demonstrates that humanity, as a condition, can be reformed.

related works:

-

• Milk and Blood

performance (2015-2018)

-

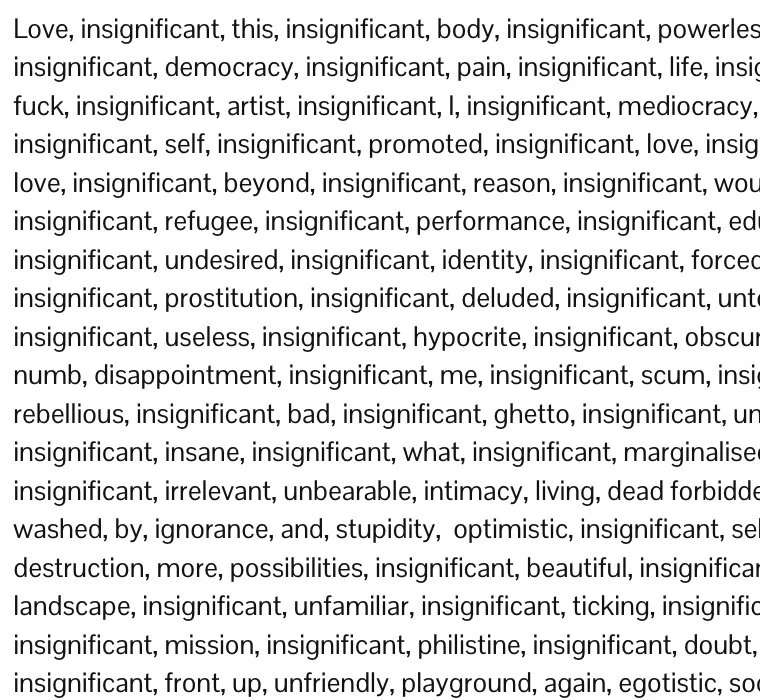

• Insignificant

text (2015)